You Won’t Be Seeing Rainbows Anymore by Tom Holloway

MTC Lawler Studio, Southbank

Reviewed on September 4, 2010

Life By Numbers.

Placed under the microscope for our pleasure and pain, as the temperature rises, the lives of six ordinary people intertwine in a human chess match

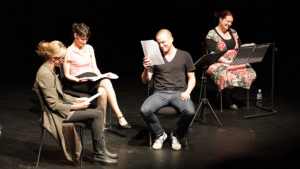

On a bare stage without the added magic of scenery, smart lighting or elaborate costumes to hinge on, in a play reading, both the actors and the audience are at the mercy of its writer’s words. The flip side is, however, there are no distractions. An author’s vision remains simple, clean and unfettered, thus easing the rules of the game into place.Under the auspices of MTC and The Joan and Peter Clemenger Trust, this series was created to give local writers the opportunity to have their works heard (often whilst still in development) before an actual audience. The next step forward from intensive workshopping, public previews of this nature are a significant part of the creative process.

Dialogue existing only on the page is one thing, but to have a collection of thoughts given voice is entirely another. Not only can these ideas be heard, an audience’s acceptance gives greater strength to their success. Or, whether further honing down the track is required.

The third play in a trio of pieces held at the Melbourne Theatre Company’s Lawler Studio, You Won’t Be Seeing Rainbows Anymore is the new work by prolific talent, Tom Holloway. His previous pieces include Love Me Tender, Gambling, Faces Look Ugly, as well as And No More Shall We Part. Later this year, Red Stitch will be doing a national tour of Red Sky Morning.

Part political expression and part performance art, experimental theatre is an acquired taste, and here, that format is established early. Performers each referenced only by a number, give Holloway’s players an ominous hierarchy, not unlike the human rankings used in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World.

Over the course of a sweltering day in a bustling but unidentified city, we are given a snap shot into the lives of six people. Living in a decaying apartment building, the unyielding heat combined with exterior goings-on, puts its inhabitants on edge.

Several of the characters announce throughout proceedings, with loose reference to 9/11 and The Los Angeles Riots, that something terrible is about to happen. Slowly, their lives entangle like the inhabitants of a Raymond Carver short story.

Players are mostly however, both frustrated and paralyzed by their actions. The story in fact, opens with the first of its characters, One (Thomas Wright), standing atop the block, seemingly swaying between life and death. Soon, One’s actions are questioned by another character, Two (Francis Greenslade), suffering his own personal crisis.

Sparring like champion debaters, Two can’t allow One’s motives. Dogmatic, he keeps at him. Finally distracted, One moves back from the edge, his focus broken.

Sitting either side of a metaphoric wedge, there is emotional disconnect between One and Two. They give voice to their thoughts, meanwhile mumbling their fears and dreams, but only vaguely acting on them.

If that interplay sounds familiar, it is a device Samuel Beckett used in works such as Endgame and Waiting For Godot. Especially here when one of the characters sighs, “It feels like something is going to happen. Something should happen.”

Later, when Two asks Four (played by Jan Friedel) if she loves him, her monotone reply is, “I love what you do to me.” In this way, she both answers and dismisses him.

There is however, a Zen undercarriage to the characters exchanges.

At key points in the show, the director, Matt Lutton, reads off stage cues to pre-empt the action. Like Svengali, his presence is significantly omnipotent.

When Lutton describes that the couple start kissing passionately, instead of them just doing so, on command, they start rolling their tongues side by side with hilarious, mechanical vigor. Both Jan Friedel and Francis Greenslade understand and work this scene perfectly.

Should this device (and others like it) survive the limitations of the reading, their irony will have tremendous impact in the finished production.

Act Two digs for an unspoken truth. In this nightmare state, players interact with deathly results. Five (Roz Hammond) after being left by Two, meets Six (Dylan Young). A metronome pounds heart-like in the background. Their carnal impulses leave Six dying, and Five hysterical.

In the throes of death, the music of Roy Orbison plays as a backdrop. Completing the puzzle, it is from one of his songs that the play’s title is borrowed.

For the full production, it has been suggested that the actors will be miming, dancing, or singing karaoke-style. Here however, each character stands rigid, their stare hypnotically middle distant. In turn, as five of the six players collapse in various ways, like the way songs are used in many a Dennis Potter telemovie, The Big O’s music becomes an anthem for lost souls.

It will be interesting to track how Holloway’s powerful new work evolves from here.

Image Source: Melbourne Theatre Company